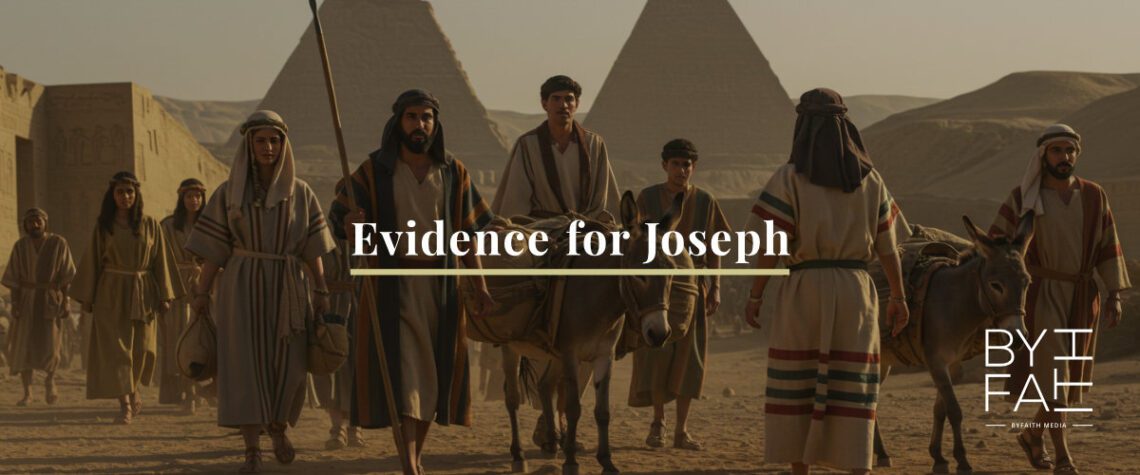

Archaeological Evidence for Joseph and Israel’s Sojourn in Egypt

Uncovering Joseph and the Hebrew Slaves in Egypt

Deep in the sands of Egypt, where the Nile whispers tales of ancient civilisations, a question lingers – have the Hebrew slaves of the Bible been immortalised in the art and ruins of this ancient land?

Therefore they set taskmasters over them to afflict them with their burdens, and they built for Pharaoh supply cities, Pithom and Raamses

– Exodus 1:11

Archaeological discoveries, from vibrant tomb paintings to the sprawling remains of a lost Semitic city, offer tantalising clues that echo the biblical story of Joseph and his family – enslaved, yet enduring, in the shadow of the pharaohs.

Walk the Bible, Episode 12

Joseph and Israel in Egypt, Archaeological Proof Documentary, EP 11

Don’t forget to Subscribe to Walk the Bible on YouTube & follow us on social media @walkthebible to keep up-to-date with the latest episodes from Walk the Bible.

A Vibrant Migration Frozen in Time

In the rock-cut tombs of Beni Hassan, a breathtaking scene captures a moment from the distant past, a caravan of Semitic travellers – men, women, children, and animals – journeys into Egypt. Painted around 1900 BC, during the time of Joseph, these figures stand out vividly against the darker-skinned Egyptians surrounding them. The ancient Egyptians painted these people with fairer skin, sharp features and pointed beards to mark them as foreigners, and their multicoloured garments evoke the biblical coat of many colours given to Joseph.

Now Israel loved Joseph… he made him a tunic of many colours

– Genesis 37:3

One man even carries a hand-held lyre, reminiscent of the instrument David played before the Ark of the Covenant. This vivid tableau feels like a snapshot of Jacob’s family, stepping into Egypt as the Bible describes, their distinct identity preserved in the brushstrokes of an ancient artist.

A Semitic Stronghold in the Land of Goshen

In the Bible’s Land of Goshen, where Joseph settled his family (Genesis 46:28–34), archaeologists have unearthed the sprawling remains of Avaris, a Semitic city that once thrived in the Nile Delta. Known today as Tell el-Dab’a, Avaris was a bustling metropolis around 1670–1550 BC, its foundations revealing homes built in a style later found in ancient Israel.

Then he sent Judah before him to Joseph, to point out before him the way to Goshen. And they came to the land of Goshen

– Genesis 46:28

Astonishingly, royal seals unearthed here bear the name Yacob-har – the biblical ‘Jacob’- alongside another, Sakir-har, echoing ‘Issachar,’ one of Jacob’s sons, meaning ‘there is a reward.’ These discoveries suggest that the Semitic rulers of Avaris, known as the Hyksos, may have been the family of Joseph, rising to power as the Bible recounts.

All the persons who went with Jacob to Egypt, who came from his body, besides Jacob’s sons’ wives, were sixty-six persons in all

– Genesis 46:26

Remarkably, Avaris and the nearby city of Ramesses lie in the very region the Bible identifies as Goshen. The Hyksos, a Semitic people who ruled as Egypt’s 15th Dynasty, left behind evidence of their prominence – until their world came to an end in an exodus.

The Tomb of Joseph?

In the ancient soil of Goshen, beneath the ruins of Avaris, archaeologists unearthed a tantalising mystery: a tomb of a Semitic man, marked by a shattered statue of a figure in a vibrant, multicoloured coat – a garment echoing the biblical tale of Joseph. Unlike typical plundered graves, this tomb was eerily empty, its bones removed, defying the habits of ancient tomb raiders. Could this be the long-lost resting place of Joseph, the Hebrew vizier whose bones, were carried away during the Exodus? This enigmatic find at Tell el-Dab’a continues to spark archaeological and theological debate.

Moses took the bones of Joseph with him, for he had placed the children of Israel under solemn oath, saying, “God will surely visit you, and you shall carry up my bones from here with you”

– Exodus 13:19

From Power to Persecution

According to ancient Egyptian records, around 1550 BC, Pharaoh Ahmose I expelled the Hyksos from Avaris, casting them out in a mass exodus that mirrors the biblical departure of the Israelites. After their expulsion, the Hyksos vanish from history, leaving behind only their ruined city and a lingering Egyptian resentment toward ‘Asiatics.’

So the Egyptians made the children of Israel serve with rigor and they made their lives bitter with hard bondage – in mortar, in brick and in all manner of service in the field

– Exodus 1:13–14

Could these Hyksos be the Hebrew slaves of the Bible? The similarities are striking: a Semitic people, settled in Goshen, powerful yet ultimately subjugated. Others suggest the Hebrews lived among the Hyksos – their departure triggering the fierce persecution described in Exodus.

- The Book of Revelation Chronology: An End Time Timeline by Paul Backholer

- Biblical Archaeology

- Where was the Bible’s Red Sea? Where did Moses cross Yam-Suph?

- A Third Temple in Jerusalem will be Built

- The Battle of Armageddon and the Return of Jesus Christ to Israel

- 666 – The Mark of the Beast and the End Times Antichrist

- Six End Time Signs for Israel

- 20 Signs of the End Times

- Christians will be Raptured before the Tribulation

- The Seven Trumpets in the Book of Revelation

- The Tomb of Jesus

- The Bible’s Joseph in Ancient Egyptian History: Evidence for Joseph from Egypt

- Borders are Good! The Bible, Immigration, Refugees & Economic Migrants

- Is Being Woke Christian or Antichrist?

- The Collapse of the United States: A Time-Traveller from 1950 Visits the US in 2023

- Homosexuality, Promiscuity and the Collapse of Society: Follow the Science

- The Forgotten White Slaves and the Ignored History of Slavery Worldwide

- What is a Woman? And why it Matters to Christians

- Why Abortion is Wrong

- What is the Rapture?

Ancient Egypt’s Painted Tombs and Lost Cities

This brutal reality of slavery comes to life in the tomb of Rekhmire, a vizier in ancient Thebes, dating to the 15th century BC. Here, vivid paintings depict Semitic men, identified as ‘captives,’ toiling under the watchful eyes of Egyptian overseers. One scene shows a Semitic man shaping bricks, while an inscription declares, ‘The rod is in my hand, be not idle.’ The echo of this command resounds in the Bible, where the Israelites are beaten for idleness and failing to meet brick-making quotas (Exodus 5:14). These images, etched into the walls of an Egyptian tomb, capture the suffering described in Scripture, as the Hebrews laboured under the lash.

For they are idle; therefore they cry out, saying, ‘Let us go and sacrifice to our God.’ Let more work be laid on the men, that they may labour in it

– Exodus 5:8-9

As we see in Rekhmire’s tomb, ancient Egyptians used distinct colours in their wall paintings to differentiate various groups, reflecting cultural and regional identities rather than modern racial categories. For instance, they often depicted Semitic Asiatic people with yellow skin, Egyptians with reddish-brown tones, Nubians with darker hues, and Libyans with lighter skin and tattoos. These artistic conventions were symbolic, tied to geographic origins and cultural distinctions, not a systematic racial hierarchy as some interpret today.

Hatshepsut and the Foreign Rulers of Egypt

The Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut (1489–1469 BC) provides additional context on the exodus and disruption caused by the Hyksos. In an ancient temple we found this inscription:

I have restored that which had been ruined. I have raised up that which had gone to pieces formerly, since the Asiatics were in the midst of Avaris of the Northland, and the foreigners amidst them, overthrowing that which had been made

– Temple of Hatshepsut, Speos Artemidos

Her inscription, recorded about the Hyksos’ expulsion, reveals Egyptian disdain for these ‘Asiatics,’ a sentiment that mirrors the pharaoh’s fear in Exodus 1:10 that the Israelites might align with Egypt’s enemies. This negative portrayal underscores the shift from the Hyksos’ prominence to their descendants’ enslavement, fulfilling the biblical prophecy that Abraham’s descendants would be afflicted in a foreign land (Genesis 15:13).

A Story Written in Stone and Scripture

While some scholars dismiss the connection between the Hyksos and the Israelites, the evidence resonates deeply. The Hyksos’ Semitic origins, their settlement in Goshen, the timing of their arrival, and the artefacts unearthed at Avaris align closely with the biblical account of Joseph and his family. The Egyptian memory, even today, associates the Hyksos with ‘Jews’ and a lingering echo of the Israelites’ presence in Egypt.

These discoveries are therefore more than archaeological curiosities – they are a bridge between faith and history. The painted travellers of Beni Hassan, with their multicoloured coats, evoke Joseph’s arrival in Egypt. The Semitic city of Avaris, with its Israelite-style homes, the Semtic tomb and royal seals bearing biblical names, aligns with the rise of Jacob’s family. The brick-making slaves in Rekhmire’s tomb, beaten for idleness, reflect the Israelites’ oppression. Whether the Hyksos were the Hebrews themselves or a broader Semitic group among whom the Hebrews dwelt, the evidence points to a profound truth: the biblical narrative of enslavement and deliverance is rooted in the sands of Egypt.

By Paul Backholer. Find out about Paul’s books here.

Don’t forget to Subscribe to Walk the Bible on YouTube & follow us on social media @walkthebible to keep up-to-date with the latest episodes from Walk the Bible.