L.S. Lowry, Faith and Art

Jesus said, “If anyone desires to come after Me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily and follow Me”

– Luke 9:23

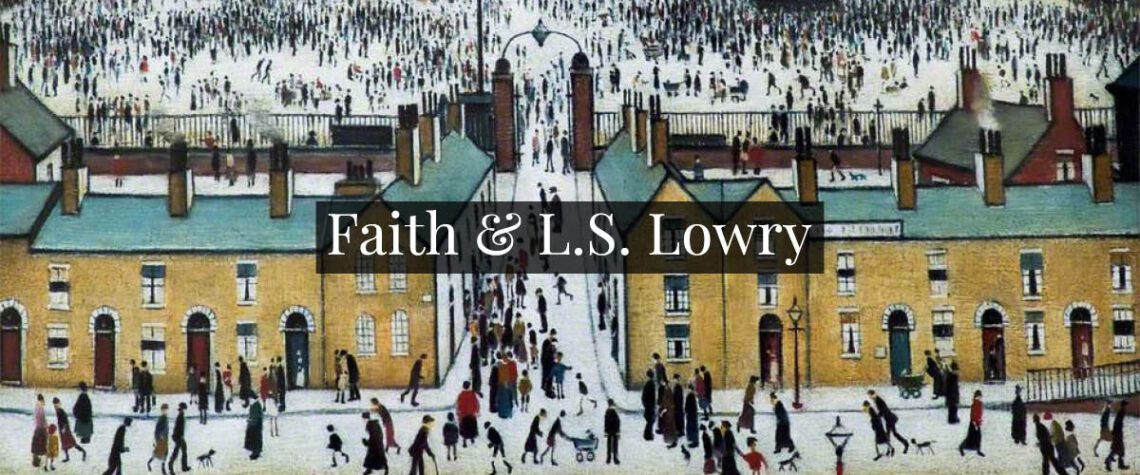

I can’t help feeling sorry for L.S. Lowry; sometimes recognition comes too late. Speaking of the people in his innovative paintings, he once said, “All my people are lonely and crowds are the most lonely thing of all.”

The young Lowry (1887-1976) was born into a respectable middle class household that came crashing down. With the death of his father, he found himself responsible to support his difficult mother and repay the family debts. All his hopes for marriage and children failed. He became a lonely, solitary figure trying to make sense of the gifts God gave him.

Raised in a Christian household, Lawrence Stephen Lowry went to Sunday School and sung hymns, as his talented mother played the organ. As life became bitter, Lowry’s faith became shadowy, but he kept a collection of sermons for reference called, The Graver Thoughts of a Country Parson. The book contains a chapter on the ‘Thorn in the Flesh’ and ‘Christian Self-Denial.’ About taking up one’s cross, the author states:

Thus the meaning of our Lord’s words is, that if any man, then or now, wishes to be His disciple, that man must make up his mind to daily self-denial, and to the daily bearing of burdens, more or less painful to be borne. It was not a smooth or attractive account of his religion that the Blessed Redeemer gave.

– The Graver Thoughts of a Country Parson by Andrew Kennedy Hutchinson Boyd, p.275

Lowry knew much about self-denial and living with a thorn in the flesh. His mother was difficult, controlling and needy. Life locked him into a relationship from which he could not be disengaged. Her good opinion was all he desired, but she dismissed his art and longed for the middle class life he could not provide.

His childhood was lonely and the sense of being a drifter never left him, but it provided him with a refreshing perspective. The poverty he was thrust into was not of his own making. He was a stranger, looking at the lives of struggling workers and freezing their image in time. He painted the story of those forgotten by society: the mill workers, terraced streets and industrial towns of the north of England.

Turn to me and be gracious to me, for I am lonely and afflicted

– Psalm 25:16

Lowry’s first paintings show talent and his perspective became anomalous, evolving to paint people as ‘matchstick figures.’ His detailed early works prove his matchstick men, which could appear simple at first, represent an artistic choice. But his mother and the critics thought his art was childish and primitive.

Today, he is viewed as a master, one willing to tell the story of those who had no voice in England.

He observed those with ragged clothes, worn shoes and dirty labouring faces. He saw the cruelty, laughter, darkness and beauty in working class lives.

He put a mirror to the chimneys, factories and crowds of labourers in the North West of England. As he aged, his darker paintings reveal all was not well. Faith indeed may have died.

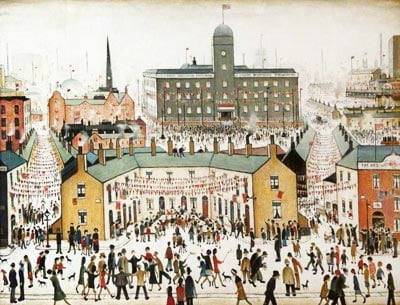

He also saw the brightness of life, capturing hope and celebration in paintings such as VE Day, 1945. But note the solitary figures, standing outside of the crowds who are lauding peace and victory.

For three decades he laboured with little success; in the day he was a rent collector and carer at home, and often at night an artist. His paintings filled with lonely stylised figures, without shadows, led to him being deemed an amateur ‘Sunday Painter.’ Thus, when money and fame came, it was too late.

The Beatles sought his works, and the British Prime Minister and the Post Office wanted to reprint his art for postcards and stamps. He rejected five great honours, including a knighthood because it was too late for his deceased mother to finally receive the respect she craved. Two years after his death, his life was celebrated in a number one hit ‘Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs’ by Brian and Michael, with St Winifred’s School Choir.

His Christian themed paintings focused on churches and their place in society. To include A Street Scene (St Simon’s Church), 1928, The Mission Room, 1937, St John’s Church, Manchester, 1938, After the Wedding, 1939, St Augustine’s Church, Manchester, 1945 and Lancashire Fair, Good Friday, Daisy Nook, 1946.

Whilst researching my book How Christianity Made the Modern World, I investigated Christianity and art for a chapter and toured many galleries. I watched non-believers stand before the paintings of Christ and hoped they pondered their eternal soul. It is a witness I thank God for.

By Paul Backholer. Find out about Paul’s books here.